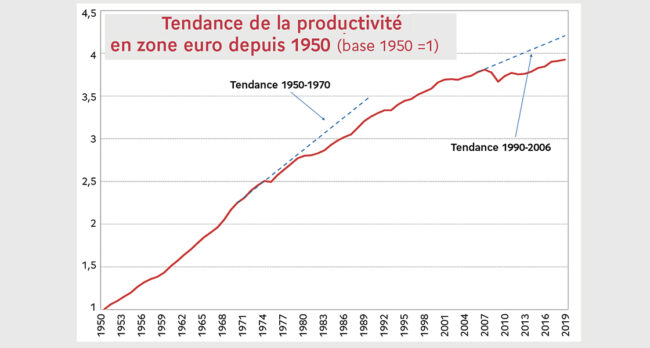

In spring 2017 (Futuribles 417) we devoted a special dossier to the slowdown in productivity gains and its consequences for the economic development of the countries concerned. While technical change was spreading rapidly through all sectors of the economy, the rise in productivity that might have been expected failed to materialize. Five years later, when the Covid crisis has substantially sped up the spread of digital technology, is this leap in productivity finally going to happen?

Antonin Bergeaud, Gilbert Cette and Rémy Lecat, who contributed to that thinking in 2017, take stock of long-term developments in productivity and the prospects that might arise not only from the effects of the Covid crisis but also from the energy crisis that is looming on the back of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. After reminding us of Solow’s paradox (‘You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics’) and the very low levels of productivity growth registered in the developed countries in the last decade, they stress the role played historically by previous crises (the 1973 oil shock and the great recession of 2009) in these developments. They go on to present the currently prevailing interpretations on the impact of the current crises on productivity. For example, the Covid crisis, as an exogenous shock, is not expected to have any notable impact on the long-term trends that were at work before 2020, and might even hasten the arrival of the long-expected productivity shock; by contrast, the energy crisis associated with the urgent need to escape dependence on fossil fuels (a crisis precipitated by the war) and with the challenge of ecological transition, which represents a distinctly more structural ‘supply-side shock’, might have an opposite effect and reduce productivity, with potentially very painful macroeconomic consequences for a country like France.